George Buck held more jobs during his Vietnam tour than perhaps anyone who did time at LZ Sherry.

Fresh into Vietnam, his first assignment took him to the 4th/60th Duster battalion as a platoon leader. After four months of action up and down the Central Highlands he went to the 5th/27th artillery battalion as a forward observer for Charlie Battery. Three months later he became executive officer of B Battery at LZ Sherry, but spent most of his time on air mobile operations. The last six weeks of his tour were relatively quiet. Lt. Colonel Crosby brought him to battalion headquarters in Phan Rang as his intelligence officer, where again he spent a considerable time in the air on recon missions.

If there is a single theme running through these many assignments it is isolation, a bloodless wound suffered by many young men who were forward observers or in small mobile units away from their comrades. Here is how George described it in an email to Hank Parker:

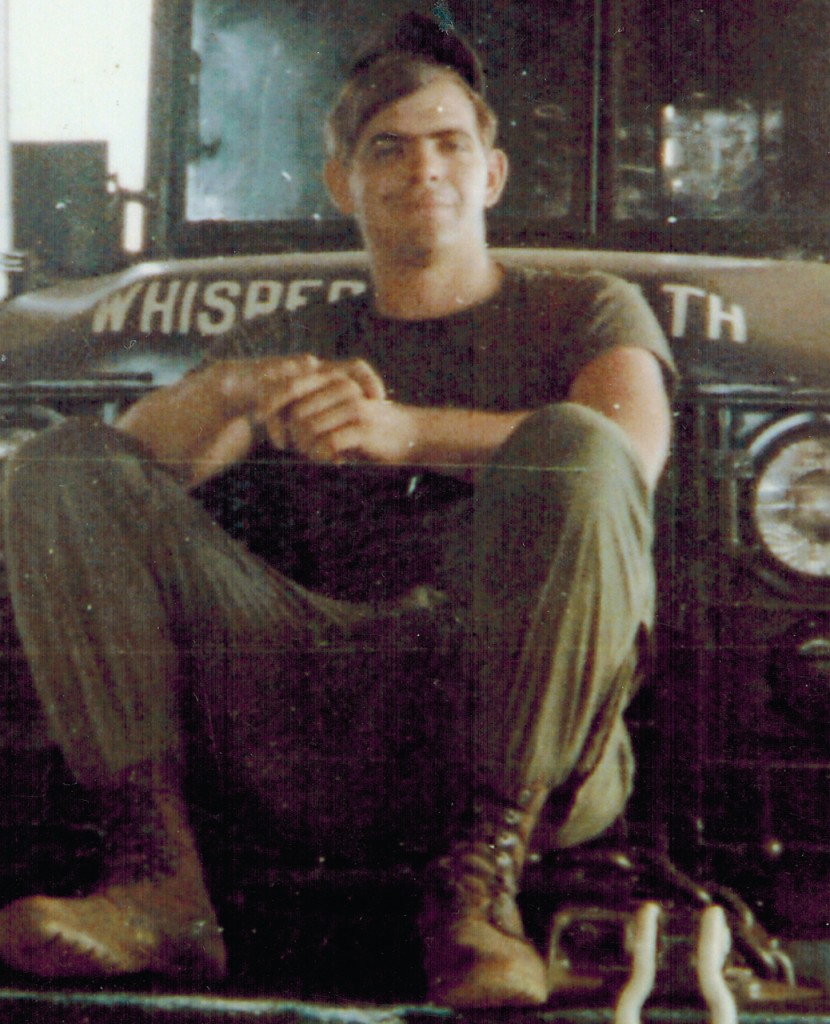

“I recall little from my four months as a Duster platoon leader and then my stints as an FO for C Battery, XO for B Battery and then the S2 job which included doing daily aerial recon around Phan Rang air base. I think one reason I recall so little is that I never had any chance of bonding with anyone. I came to Vietnam on individual orders, went to Dusters, which is a completely different MOS (military specialty different from field artillery), was isolated totally as a platoon leader with no other officers within fifty miles of me, then as an FO with a different non-U.S. unit every ten days for months, rarely shooting for my own battery, and then as XO for only a few months at Sherry, which was, at the time, a new fire base. At the battalion I think I was the only lieutenant, so I was isolated there too. The captain that flew the L19 (recon fixed wing airplane) and I became good friends, but only for about two months and then I was home again and out of the Army. It was a rather lonely existence and to top it off my jeep trailer was raided on multiple occasions and I lost my cameras and film, so I have very few pictures. I wish I had kept a diary.”

The start of my military experiences go back to my freshman year at Penn State when I was in Army ROTC. Due to an antiquated law going back to the days of land grant colleges, ROTC was mandatory for all incoming male students. If a college was given land to build its school, in return it had to have mandatory ROTC for the first two years for all male students, with an optional advanced program for the final two years. I chose the Army ROTC program, and at the end of my sophomore year opted for the advanced ROTC program. Then after I graduated on December 17, 1966 I was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in the Army Reserves.

After a few months off I reported to Fort Sill for Field Artillery Officer Basic, which lasted about ten weeks. From there I went to Fort Knox, Kentucky to the U.S. Armor Training Center. Initially I was made Executive Officer of an artillery battery (B Battery, 3rd Howitzer Battalion, 3rd Artillery Regiment), which was interesting since there were other lieutenants already in the battery. I am not sure how that happened but within a month I got bumped by a 1st lieutenant who had been in graduate school, and I spent the rest of the year as the Assistant XO.

Vietnam

The Army put you where they needed you, and not always where you had the training.

In December, 1967 I was on leave for the holidays when I got orders for Vietnam, telling me to report to Oakland, California on January 1. From there I flew to the Philippines and then to Saigon where I was under the control of USARPAC (US Army Pacific Command) RVN. I was a single assignee, not travelling with any unit, so I was not sure where I would end up. Eventually I was assigned to the First Field Forces and spent a week waiting for my unit orders. When they finally came I was surprised that I was assigned as an assistant platoon leader to B Battery, 4th/60th Air Defense battalion, which was a Duster unit and not field artillery. This was an entirely different MOS (military occupational specialty): 1174 MOS and not the 1193 MOS I was trained in as a field artillery officer.

The 4/60th Duster battalion had a chronic shortage of lieutenants. Operations reports from 1968 to 1970 list an average of just eleven lieutenants for almost a thousand personnel.

For a newly minted 2nd lieutenant newly arrived in Vietnam, taking his first command job outside his area of training would have been tough. He felt as if he knew nothing, knew no one, and would be forever an outsider – another wrinkle in the curtain of isolation that shrouded George’s year in Vietnam.

I had no clue what a Duster was all about. My only idea of a Duster configuration was the Naval guns on Destroyers and the other big ships that had exposed tubs on their sides with twin 40 mm guns mounted in them for air defense. If you were a fan of the old Victory at Sea shows, these “Duster” tubs were the final defense against Japanese suicide planes.

A Duster was an Army Air Defense weapon that became obsolete once the era of jet fighters became the norm. But it still was effective as a ground defense weapon for strong point security, convoy escorts, and perimeter defense requiring heavy direct fire support. The gun tub was mounted on an old model tank, so it basically was a tank with a tub on top and two 40 mm guns that could fire either automatically or in semi-automatic mode (one shot at a time). We also had attached Quad-50 machine gun units, so combined these platoons of Dusters and Quads were extremely effective in providing fire power superiority and eliminating large enemy assaults and concentrations in a very short time.

So one of the unique aspects of my year in Vietnam is that I was a combat commander in two different MOS categories with three entirely different weapons systems (Dusters, Quad-50s and howitzers). Fortunately the crews on these assignments knew precisely what their duties and missions were, and could function independent of any kind of direct supervision. It is why for the Duster and Quad-50 crews it was a “Sergeants’ War”.

My platoon was located along Highway 19 about in the middle between Pleiku (Battery B headquarters, 4/60th) and the Mang Yang Pass near An Khe. We were at a bridge site with defensive positions on all four corners, a Military Police shack, and an ARVN (South Vietnamese) Regional Force unit. There was also one tank from the 4th Division commanded by 2nd lieutenant John Abrams, the son of General Creighton Abrams, who had taken over for General Westmoreland, and ran everything in Vietnam. Lieutenant Abrams’ tank was my main defense against a frontal attack on my Duster, and I reciprocated with my Duster providing cover for his tank and defensive position. On the day Lieutenant Abrams became a 1st lieutenant his father flew in and pinned his silver bars on him.

Acosta and Donovan

Our Platoon Leader was a 1st lieutenant from the west coast who was really laid back and a nice guy, what you would describe today as a “surfer dude”. We got along, but I had some very definitive security issues that concerned me, though I was careful not to rock the boat too much. I didn’t believe that we had enough wire out on our perimeter, and I didn’t like the Montagnards (mountain tribe people) coming into our garbage pit rummaging around for scraps. Too much could be salvaged for land mines and other things.

A major issue was that every morning we were the first on the highway, because we had to go up to a 4th Division base camp to get our hot food for the day, which was put in mermite cans (insulated food containers) to keep it warm. Highway 19 had been paved at one point but now it was full of pot holes, so the convoys rode on the side of the highway which was all dirt and easy to lay mines in by the enemy. I wanted our tracks and vehicles to stay on the paved portion since it could not be mined easily, but unfortunately I was not making much of an impact being only the assistant platoon leader.

Two weeks into my tour my first major tragedy and setback occurred. Two of our men driving my jeep up to the base camp for our daily chow were riding along the side of the road and ran over a mine, killing both instantly. It is something that I will never forget. Names and people from my tour escape me, but I remember Acosta and Donovan. It was such a sobering event, the loss of two men, the failure of leadership on my part, something I would live with for the rest of my life, and I was only 22 years old.