Leaving Vietnam Was Harder Than Going

Leaving Vietnam Was Harder Than Going

When you get short you think this is not the time to die. There was a guy on the quad-50 machine guns right behind my bunker who died the week he was supposed to go home. Those guys were always the first to shoot when we got hit, the first to get the action going. During mortar attacks this quad-50 was my alarm clock most of the time; when it went off it shook the ground. During a mortar attack he got hit with shrapnel that went underneath his helmet, hit him in the temple and killed him dead.

A few days before I was supposed to leave LZ Sherry for home, in early May of 1970 when LZ Betty got overrun, I was outside again – it was night but don’t know if I was in the can or not – and they started walking the mortars in on us. The explosions were coming closer and as I ran away from them I crashed into one of the bunker walls I didn’t see in the dark and broke my nose and busted my front teeth out. Still I did what I was supposed to do: I checked on my operators and then went to my fighting position and made sure we had guys out there. This one guy in his fighting position wouldn’t put his head up, so I had to go in there and rouse him up to start looking. I then went to my roof top observation post to look for mortar splashes, then came back down again and was running around through all the smoke and craziness.

I ended up getting sulfur burns on my face and hands too that night, which really hurt if you’ve ever had a sulfur burn. I don’t know how it happened, but it must have come from someone popping a smoke round somewhere and me not knowing I was right next to it. That was so much worse than my nose and teeth, because it really hurt. The next day – I’m really short by now – I talked to the medic and said my face and hands are burning. I’ve got this hole in my lip and my teeth are broken, but what I really want is something for this burn. He said, “I can’t do anything for you. They’ll take care of your teeth when you go home.” He told me not to get treated in country because I’d go to a hospital and be in the Army for another 30 days. I could not deal with that. I can tough this out. In three days the burns on my hands and face turned black.

I’d been on LZ Sherry for six months and I had not been paid for the last four. It was like they lost me. I never heard from my battalion anyway; those guys never left headquarters. (Jim’s chain of command stretched 300 miles north to An Khe where the 8th/26th Artillery – Target Acquisition – had its headquarters at Camp Radcliff.) I’d rarely see anyone from battalion in the field. The only time we’d see any brass on the firebase it seemed to me is when we took casualties. They’d come down and they’d be all over you for a few hours, quizzing you about this and that.

When I had about a week to go I learned battalion had sent a message down for me to go home 30 days before that, but by the time it had gone through six or seven hands it was so garbled nobody knew what it was. I would not have gone back anyway, because if I had to spend any time in the rear I would have been busted back to private. My replacement was there and he said I could go anytime I wanted, but I said I would stay till the last minute, and then hopefully I’d stay out of trouble when I went back there, because the rear areas at that time were beyond beyond. They were crazy places and I knew I would not fit in.

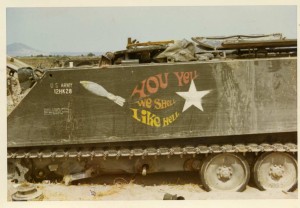

A part of my attitude about the rear came from a trip I made back to Camp Radcliff from Sherry with one of my guys who was going up before a promotion board. It’s a long way, a number of chopper rides to get back up there. We finally get there and we look awful, we’re dirty, we’re carrying our weapons and all our stuff with us down a road through the camp when this jeep goes by us maybe 50 feet when all of sudden we hear the screech of brakes. It goes in reverse back to us carrying a new-dude major. You can tell he’s a new-dude because his fatigues are brand new. We salute him and then he chews us out for not walking in step. This kid and I looked at each other and said, “Jesus Christ, what is the matter with these people?” We did everything we could not to draw on him. That’s why I was happy as a clam in the field. If they made me go back there for any length of time I would be in trouble. I had enough trouble as it was keeping my mouth shut.

I have all my stuff packed up and I’m ready to leave. They mounted the convoy to LZ Betty. We were not aware of everything that had gone on at LZ Betty, at least I wasn’t.

In the early morning hours of May 3, 1970 an NVA battalion of five companies in consort with five companies of VC, a force of 350, overran LZ Betty. They killed seven U.S. soldiers and wounded thirty-five, leaving behind fourteen bodies of their own they could not carry away.

All I remember is that the sun was beating down on me and that it was really hot on that convoy. My face was burning so bad that I jumped off and went over into a rice paddy and put mud on my face to cool it. When we finally got to Betty it was going to be awhile before my chopper would leave to take me to Phan Rang. I went over to the MASH unit to see if they had some sort of salve they could give me. The medic there looked me over and said, “We really don’t have anything that’s going to help you. We could admit you, but if we do you’re going to be here for awhile.”

I said, “I’m going home, man.” So I went to Phan Rang, was able to visit with my warrant officer friend who extended so many times, and found another chopper ride up to Camp Radcliff. I walked into the battalion headquarters, went into the top sergeant’s office to check in. He looked up and asked me what I was doing there. I said, “I’m going home.”

He said, “You went home a month ago.”

At which I erupted. I was so mad I went into a tirade, for them not to know where their people were. He was a good ol’ sergeant major and he let me vent on him, to the extent that I almost got out of line. He tried to explain, but I wasn’t having any of it. He finally told me to cool my jets before I ended up in jail. I said, “Just get me out of here as fast as you can.”

You know how you had to have a reenlistment talk. I think mine was the fastest there ever was. I said it was just not for me, and he said, “I’m going to get you out of here as fast as I can.” I really appreciated that.

The sergeant major, who was a good guy, wanted me to stay another day for an awards ceremony. He said I got a Bronze Star, which I guessed was from my time at Dak To. He also looked at my burnt face, which was all black and pink. I looked pretty awful. He asked me what happened and when I told him he wrote it all down and said at the awards ceremony I’d be getting a Purple Heart too. I said, “I don’t want to be here, I want to go home. I have to get out of this place. Even though it’s a bigger base than Sherry I do not want to be here.” So he gave me the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart medals, and said the paperwork would catch up with me later.

He then sent me to supply to turn in my stuff. Of course coming out of LZ Sherry all your stuff was filthy, and most of it wet. I talked to this supply sergeant and he tells me he isn’t going to accept my stuff. I have to go someplace and clean it. Once again I erupted, got into a big tet-a-tet with him. He called the sergeant major and said we were coming to blows. I don’t know what the sergeant major told him, probably to leave me alone, but he changed his mind and said he’d take my stuff and signed me out.

So I got a chopper down to Cam Rahn Bay, where I sat there for three days in a barracks where everyone waited for a flight home. Every three or four hours there was an assembly, and if they called your name you were getting on a plane. I was so afraid … If you did not answer that call you got put to the end of the line again. I thought this sergeant major was going to get me on an early plane, but that was just insane thinking. I stayed up literally 24 hours a day for three days going to these assemblies because I was afraid to go to sleep and miss my call. Finally I fell asleep due to exhaustion. When I woke up I saw there was an assembly going on. I ran down the barracks and heard my name called. Oh my god I almost missed it! I slept the whole trip home and don’t remember anything about it.

The Shortest Vietnam Tour Ever

I got to California where they were going to check me out. They asked me if I was alright and I said yes because I didn’t want anything to hold me up. They had my pay figured out by then. I stayed in uniform and went back to Omaha where I checked into the VA to have my teeth fixed. The experience at the VA hospital was so bad that I swore I’d never go back, and I did not for 38 years. But then recently I thought I should get into the system because of exposure to Agent Orange and what if I got cancer some day from it. I applied to the VA and was shocked when I got a letter back denying me service. Vietnam vets were supposed to be golden. That’s when I found out that my discharge papers had the wrong dates. My discharge said I arrived in Vietnam one day, and left the day before. It said, “VN SERVICE: 20 May 1969 – 19 May 19, 1969.” I had never paid any attention to it. Here’s the Army doing it to me again. I decided I’m just not going to think about it any more.

Years later I ran into a veterans advocate who said this wasn’t right and to come to his office and he would help me. Eventually I got it corrected by showing the VA pictures of me in Vietnam. The end of the story is the VA hospital called me up and said, “Come in.”

My discharge papers also did not have my Bronze Star Medal or my Purple Heart. We put in another appeal for the medals, which resulted in the Bronze Star being recognized but not the Purple Heart. The end of the Purple Heart story is I could not prove my injuries were the result of hostile enemy action, so I gave up. If that’s the worse thing that ever happens to me, what the hell.