Welcome to LZ Sherry

The first week at Sherry they put me on a mine sweep to clear the road for a convoy. My warrant officer comes to me and says, “Look, we’re going to do a convoy into LZ Betty. We can’t order enlisted people to be on the mine sweep, but you’re a senior NCO (non-commissioned officer – a staff sergeant), so we can order you to do it. You’re gonna have to be on the mine sweep.” I’m thinking these fuckers are out to get me.

I got a five-minute orientation on how to probe for a mine with a bayonet, going in sideways and not straight up and down which would set off the mine and blow you to bits. Out on the sweep when the guys on the sweeping equipment would detect something, they would set it down on the spot where they got the strongest signal and make a circle in the sand. And then from behind them two or three of us who would come up and probe into the ground. That was the scariest thing I ever did, because you had to find something, you could not leave that spot until you found something. I can’t tell you how scared I was.

This went on for miles. It’s a thousand degrees, and you’re sweating like a pig anyway. I found buried pieces of shrapnel but never a mine. Some guys found stuff they couldn’t identify and they ended up blowing them in place. The whole idea was that if you don’t do this right you’re going to kill either yourself, or the guys coming behind you. So it was an important job. I only had to do it once. I never had to do it again. I think they were just testing my metal. Quite frankly though, I was a wreck. The whole time I tried not to let it show, and you got to the point where you wanted to stay with one find, so you wouldn’t have to go to the next one where you might blow yourself to pieces. It was a nightmare.

After that they never made me do it again, but I would have done it. Yeah, after you do something once you realize you’re probably not going to die. Then they started doing something else on convoys. They’d take a Duster that was always on the convoy with you (heavy tracked vehicle with twin 40 mm cannons) and they’d crank that thing up as fast as it would go and hope that if they hit something they’d be past it by the time it went off. They called it thunder running. They’d thunder run on the side of the road, not on the road itself, and the convoy would follow in its tracks. It worked pretty well when the rice paddies did not come up to the road. I was friends with the Duster guys and sometimes they’d let me ride between the two cannons. It was the most comfortable place to sit, with your butt between the cannons and legs hanging over the sides. It was really cool, also because there was a lot of iron between you and the road.

Friendless

When I came to Sherry from up north I traveled with this first lieutenant. It was a long way south involving of helicopter jumps, which gave us time to talk. I’m wondering why they’re sending him to Sherry. He confides to me that he had gone to Australia on R&R, caught a case of VD, and this was his punishment. At Sherry he and I became pretty close. A month later they sent him back, and I felt abandoned.

The only other real friend I had at Sherry was the warrant officer in charge of our other radar unit. (There were two radar sections at Sherry, counter-mortar and anti-personnel.) He was a really good warrant officer and could not have been nicer. He was career Army and kept extending in Vietnam. Maybe part of the reason was he had girlfriends all over the world, and it turned out he also had a wife in Taipei. Because the radar was down and not working most of the time he and I would sit and chit-chat for hours on end. His most interesting stories were about his girlfriends. Or we’d sit and look at the equipment schematics when there was a problem. I would say, “It has to be this part right here,” and amazingly I was right sometimes. After six weeks he leaves, and I feel really abandoned. Now I got nobody.

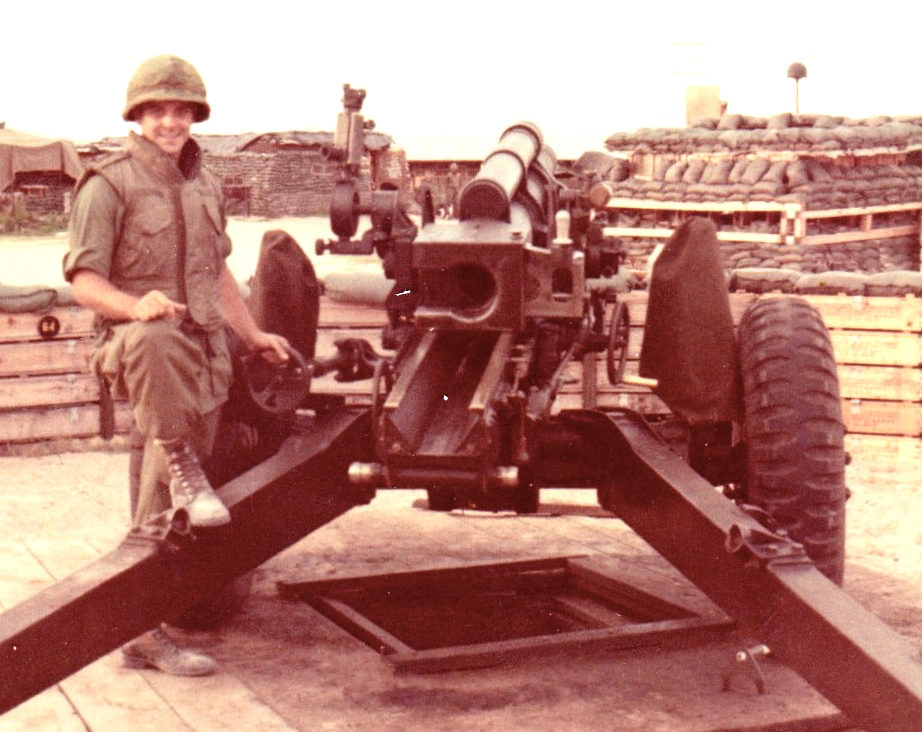

Staff Sergeant Scavio making a new friend

The Wrestling Match

The other NCOs in the battery did not like me because my radar section did not do anything to support the battery, like pulling guard duty shifts at night. Supposedly our job was already 24 hours a day. Plus I looked like I was 12 years old, and here I was a staff sergeant. They were constantly doing shit to me. They didn’t realize I was the youngest of four brothers and wasn’t going to take anything from them.

During mortar attacks the radar crews had specific duties. Only a couple of operators stayed in the radar bunker and everybody else took up positions in the small fighting bunkers on the berm (the earth mound surrounding the firebase). On top of one of our radar bunkers we built another observation bunker so we could get up and look for mortar splashes so we could run out and get a back azimuth for a target. If I was not up there I would be checking my guys in the fighting bunkers, which always made for comic relief because they’d be hiding as close to the ground as they could get afraid to put their heads up. I literally had to kick some ass, “You’re supposed to be watching!”

But I’m no hero. I had not been there very long and was relieving a young buck sergeant who was leaving. He was a good kid. He and I were up in the observation bunker during a mortar attack looking to see if we could find some splashes. All of a sudden a mortar lands really near by us. He and I got into a wrestling match to see who could get under the other guy. It was like, holy shit, they’re wired in on us. He didn’t want to get killed, and I didn’t want to get killed. It was an all out struggle to get to the bottom of the bunker and leave the other guy on top. We laughed about it later about how crazy we were because probably both of us would have been killed anyway.

From Jubilation to Panic

It was early in the morning and somebody spotted half a dozen NVA regulars in uniform straight out from the Quad-50 machine guns behind the radar section. There was a tree line out there, just outside small arms range and also in some sort of no-fire area. They were just watching us. They knew that we knew that they are there, and that we had no permission to fire.

Every night one of the Dusters would crank up its engines, you could almost set your watch by it, and take a ride around the inner berm, just outside the first set of wire. He would take a run around, warm his engines and make sure his track was working. Well on this occasion he comes around, and just as he gets past the Quad-50 he turns his turret and starts walking rounds toward this group of NVA. Of course they pick up and start running. Unbeknownst to us this was part of a clandestine operation. The Armored Cav had circled around the back of them in armored track vehicles with 50 caliber machine guns. Whoever orchestrated this thing planned to push the NVA into these guys. As this started happening, a bunch of our guys jumped on the berm and started cheering.

Now the NVA are between us and the Armored Cav. The next thing you know the Cav open up with their 50 calibers. With a range of 2,000 yards the 50 caliber rounds start coming onto the firebase. When everybody realizes what was happening all the cheering stops. They’re diving for cover, screaming and yelling. In a second it went from jubilation to panic.

Oops

Every night the major from S2 Intelligence would call down from battalion and tell us to aim our radar this way or that way. The radar unit had a very narrow band so that you had to be looking right at something to pick it up. The exercise didn’t make any sense and we hardly ever picked up anything.

We took a beating one night with casualties. The next day of course the world is all over you. I am in our bunker that holds the big map where we plot mortar locations. It’s in the morning and it’s ungodly hot, 100 degrees by eight o’clock. If you moved at all you sweat like a pig. I have my back to the door looking at the map, no shirt on, when someone comes in and says, “How come you guys didn’t pick up any targets last night?”

Without looking around I say, “It’s because of the horseshit intelligence we get around here. They tell us to look one direction, and of course the mortars come from another direction. So what do you want?” I turn around to see the S2 major. I didn’t worry about it because these guys from battalion would show up, chew you out for a little bit, and then they’d be gone and you’d probably never see them again.

A Little Privacy Please

From the time I got into the Army I was not one of these guys who could go into the latrine and sit with half a dozen guys and take a dump. It was not in my DNA. During all my training at Ft. Sill – Basic, AIT and ACL – my favorite thing was fire guard duty at night.

Many of the training barracks at Ft. Sill were drafty WWII clapboard structures originally intended as temporary barracks. By any standard they were enormous tinderboxes. Trainees rotated one hour shifts during the night, with buckets of sand lining the walls in case of a fire.

I liked fire guard at night because I could get to the latrine with nobody around and take a poop. Before Sherry when I was out in the field up north I could always find a tree somewhere. At Sherry I’d wait till two or three in the morning, find the latrine which was close to our radar bunkers, and get nice and comfortable. Soon as I settled in, sure as shit something would happen. I can’t tell you the number of times I got caught in that latrine during a mortar attack. That latrine was not much protection, just plywood walls and a corrugated tin roof. You did not want to be in there with mortars falling.