HANK PARKER

Part Ten

Skeleton Crew

After the departure of our captain the night of the August 12 attacks, I take over as battery commander. I am still a first lieutenant, but four weeks later move up to captain. During that period the battalion commander comes out to Sherry to give me a Purple Heart for wounds I got at LZ Betty seven months earlier.

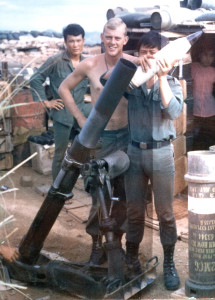

Now we are dangerously shorthanded at LZ Sherry. Two guns and their crews are still out at Outpost Nora. We lost another gun and ten men on August 12. That on top of the losses from the pounding we’d taken during July and early August. So out of a full strength battery of six guns and 120 guys, we’re down to three guns and 67 guys at Sherry. A full gun crew is eight guys, and we are struggling to find four for a gun. We have to suspend R&Rs, and I can’t send guys back to Betty who are not badly injured. Can you imagine when you’ve got that few men and you have to run a convoy? That’s leaving the battery really vulnerable. Fortunate for us the enemy never wanted to make a daytime attack.

Replacements are coming in, but they know nothing about artillery. That’s when I start to train cooks, motor pool technicians, fire direction people, and even the radar guys on how to handle a howitzer, especially direct fire with beehive (tube lowered to level and loaded with a fleshette round). I fully expect we were going to have to use them against a ground attack. I move a howitzer to the perimeter where we can practice. We have contests sighting directly through the bore of the tube to hit a target, and on one occasion a cook wins.

I am nervous and wound tight. When the sun sets I start moving the Duster 40 mm cannons and Quad 50 machine guns because I know that gives the enemy pause. They’re not going to come in under a Quad 50, or even a Duster. The crews get ticked at me over moving every night because they like to settle down in their little hooches. I say, “Hey, this is for your protection too.”

In the middle of the day I see a group of Vietnamese men and women out in the rice paddies digging like it is a burial. I suspect it’s not, so I lower a howitzer, bore site it, put a round in and I fired right over their heads. The shell explodes maybe a hundred yards behind them. The message was you can’t do that in the daytime, and if you do it at night I’m going to put the round on top of you. The province chief raises hell with my superiors at Betty because we are under orders not to fire at anyone unless first fired at. I get a call, “You don’t do that.”

I say, “I will do that. My job is to protect my battery.” Had shrapnel hit them I probably would have gone to jail.

Always, always I stress with the guys how vulnerable we are. A little example, we take our laundry into Phan Thiet to Liz, a beautiful French-Vietnamese woman in a purple dress. I know she takes note of the names on the uniforms and that information is passed on. Only a few guys don’t want to pay the extra few bucks and do their own laundry. I tell the guys the enemy knows exactly how many people we have and they know us by name. Remember the Viet Cong own this area. We got to be sharp.

August 28

Again an accurate mortar attack. The first round hits the trail of Gun 5, knocking out the gun and causing casualties. Andy Kach is with PFC Rodriquez in the guard tower returning fire when a mortar hits on the sandbags in the tower and blows both of them to the ground, maybe 20 feet below. Rodriguez is blinded by the sand, which is not unusual. Guys would be peppered when the mortar exploded in the ground, and that can be a serious injury. I know for Rodriquez it is. He takes it full in the face and now is buried under a pile of sandbags. Andy brings Rodriquez to the medic and then returns to the tower. He digs out the M60 machine gun and continues to lay down a base of fire. That is an individual act of valor because now if the enemy are going to get in they have to deal with his machine gun.

That is when I say to Doc, “Can he still manage a gun?”

Doc says, “I think so.”

I ask Andy, “Can you go back to duty?”

He says, “Yes sir, I can do it.”

I do not realize the significance of his injuries because they are not visible. They are in his jaw and teeth. In a day or two his jaw is swollen and he can’t eat, so I send him back to Phan Thiet, and then to Phan Rang for treatment.

Andy and the guy hurt on Gun 5 eventually come back to the battery, but Rodriguez goes to the states for treatment and never returns. For now we’re down another three guys. Soon after we have another attack that wounds Judson, our barber, and we send him to the rear. We’re down to half strength and under constant attack, but I love this little firebase. I am a captain now and assume I can continue as battery commander. Let me keep the battery, I am feeling. But that’s not the Army’s way.

USS Boston

Two weeks after I am made captain they send me to the battalion Tactical Operations Center at Betty. I clear grids and coordinate the fire of seven artillery batteries, standard fare for that job. But I am also put on orders as an aerial observer (AO – does reconnaissance and calls in artillery fire – a dangerous job). I have survived the war so far; I’ve been a forward observer out with two infantry battalions, I’ve been a battery commander, I’ve done my duty. Normally you don’t need official orders to be an AO, you just go out and do it. But this is for a specific mission to fire the USS Boston, a heavy Naval cruiser. The mission is going to take place in a week and I’ve only got 30 days to do, I’m short. I say, “No I am not going to be an AO. Let Lieutenant Bud Domagata do it. He’s our AO. Hell, I’m a captain now!” They want me because I had walked the target area as an forward observer and they want the AO to be someone who knows the area and can adjust fire.

They fly me out to the USS Boston in a little helicopter.

Titty Mountain in the background off her stern

I’m in my jungle fatigues and I’ve got my maps and compass and grease pencil. As I set foot on deck they salute me and say, “Good morning, lieutenant.” I think, can’t these guys see I’ve got captain’s bars? (In the Navy a lieutenant is of equal rank to an Army and Air Force captain.) They take me to the mess hall where I have breakfast with the commander. There is crystal and china, and you have Filipino waiters in little white jackets serving coffee. I’m thinking, What is this?

After breakfast we go to the war room, and I’ve never seen so much rank in my life, so many stars on uniforms. I get out my grease pencil and my map covered in plastic. The commander says, “No lieutenant, here.” An enormous map drops down from the ceiling, the biggest I’ve ever seen, and he hands me a pointer. I show him the target grids and what we’re going to do. He says, “You’re going to be the spotter, right?”

“Apparently I am, sir.” I did not tell him that I did a little aerial reconnaissance in Hawaii, but I had never called in live fire from the air in Vietnam, much less from a naval cruiser. In fact I had never even been up in an airplane in Vietnam, always helicopters.

We fly over the area and I cannot believe it. This is a major NVA staging area. It looks like ants swarming around trucks and ammo dumps. Trail heads are fortified with heavy weapons and probably mined. I call in the first salvo and when it fires I think the ship has blown up. I mean it’s her six eight-inch guns all firing at the same time, making a ball of fire so big you can’t see the ship. The pilot says, “Holy shit.” This is his first time too doing this kind of thing. I think I feel the plane move as the rounds go by us. It scares the beejeesus out of me. I say over the headset to the pilot, “We better go higher.” Which we do, while I reach for my rosary.

The rounds are on target. I see secondary explosions, ammo blowing, petrol burning. We blow the shit out of all of it. I have never been directly over my target like that. The term awesome is used too often, but to see this is indeed AWESOME. Her call sign is Mauler, and now I know why.

Back on ship I say to the skipper, “Sir, is there anything else I can do for you?”

He says, “Yes lieutenant, there is. Can you possibly get me an AK-47?”

“Yes sir, I can get you an AK.” I go back to Betty and arrange for my AK-47 to get sent to the Boston.

Later I am back on the ship and the skipper says, “Now can I do anything for you?”

“Yes sir, you can. Have you got any steaks?”

He says, “We got a lot of steaks, lieutenant. How many you need?”

I say, “How many have you got?”

He says, “This is our last mission and we’re going back to the States. I can empty my meat lockers for you.” I bring enough steaks back to feed the guys at Betty, Sherry, I think even Sandy.

In Conclusion

Medals

I leave Vietnam with a Purple Heart, the only medal from my tour. I know Colonel Crosby (battalion commander) told me he was putting me in for a Silver Star, and Captain Wrazen said he was putting me in for a Bronze Star. But when it doesn’t happen, it doesn’t happen. I’m OK; they did their best.

I go to Ft. Sill where I am an artillery instructor. I come in in from a field maneuver and they say, “There’s an awards ceremony at noon. Come to it.” The person getting the medal ends up being me. I get a Bronze Star with V Device for Valor. Then more medals dribble in. I get another Bronze Star with V Device, but I cannot wear it on my uniform or the first one either, because the Army has to issue another medal with an oak leaf cluster on the ribbon indicating two medals. Then I get another Bronze Star, and have to do it all over again, but this time get a medal with two oak leaf clusters on the ribbon. So I’ve got five Bronze Star Medals laying around, but the only one that counts and the only one I can wear is the one with the V Device for Valor and two oak leaf clusters. Personnel is in a tizzy straightening out the flurry of new orders this entails (paperwork accompanying the medal and authorizing the medal).

I get two Army Commendation Medals. Same drill: can’t wear either medal, have to get a third with the oak leaf cluster and Correction DD 215s. I get another Purple Heart medal because the one I got at LZ Sherry was given to me without the orders, and now they have to give it to me again, this time with the paperwork. By now Personnel hates me, and it’s getting a little embarrassing for me too.

It gets worse. Each time a new medal comes they do not reissue your DD 214 (discharge papers indicating medals earned). Instead they give you a separate document called a DD 215, which corrects the DD 214. So I keep getting these Correction DD 215s in the mail.

In March of 1971 I go back to Vietnam. In less than a month when I am out with the infantry I step on a mine. It’s pretty bad and they Medevac me to Chu Lai for the first of multiple surgeries. I wake up in a bed right across from a North Vietnamese Army soldier. We both have IVs in our arms and we both lay there staring at one another, neither one willing to go to sleep. From there they send me to Da Nang, and from there to Japan.

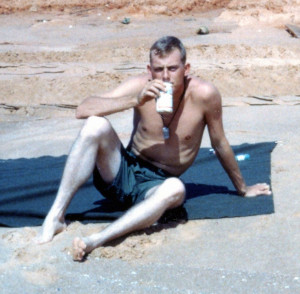

This is one of my favorite pictures of myself because it is the last shot of my healthy left foot.

Of course I get another Purple Heart and go through the drill of getting a third one with an oak leaf cluster. More important, and I am proud of this, I earn the Combat Infantry Badge. (Medal given to infantry who come into direct contact with the enemy, and highly prized) The infantry higher ups do not want to give it to me, saying I am artillery. But I am organic to the unit with an infantry MOS (official military occupational specialty). I’m now infantry. I’ve got a ton of artillery in my background, but I’m infantry and they have to give it to me.

Of course I get another Purple Heart and go through the drill of getting a third one with an oak leaf cluster. More important, and I am proud of this, I earn the Combat Infantry Badge. (Medal given to infantry who come into direct contact with the enemy, and highly prized) The infantry higher ups do not want to give it to me, saying I am artillery. But I am organic to the unit with an infantry MOS (official military occupational specialty). I’m now infantry. I’ve got a ton of artillery in my background, but I’m infantry and they have to give it to me.

In 1998, long after I am long out of the Army, the Silver Star comes through, for action at LZ Betty in February of 1969. At the same time I learn I had been awarded the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Bronze Star, dated April 20, 1971 – for service during my second tour in Vietnam. Then in 2002 the Army issues me a brand new DD 214 with all the corrections on one page.

After Word

In later years I go to see the Navy commander to whom I had given my AK-47, Captain Raymond Komorowski. I want to get the serial number off the AK in order to research what happened to the guy I captured. Unfortunately Commander Komorowski has suffered a stroke and is depressed. His son has taken it off the wall out of concern for his father’s safety, because it still had the loaded banana clip in it. He has given the AK to the local police department. I go to the police department with my request, that I only want the serial number. They say they do not have it and furthermore have no record of it. One of them I know has the AK in his collection and is telling war stories over it.