The Boys of Battery B

Peter Antonicelli

He was not trained to drive a jeep. At Ft. Sill he was about to enter Officer Candidacy School but dropped out, because it was “full of college fraternity types.” He went instead to the fire direction course.

On the phone he is quick-witted and articulate, speaking in finished sentences and polished paragraphs, enhanced by the sharp edges of a Long-giland accent. Yet he says of himself, “My entire life I’ve always been a quiet guy. If there’s a group of guys I’ll stay on the fringes of the group and add a little or just observe. I don’t dive in by the bar. That’s just not me.”

Colonel Munnelly said of him, “Peter and I talked a lot in the jeep. He and I shared some pretty hairy moments together. I got along with him real well, and he would tell me things that nobody would tell me.”

When I first got to Vietnam and assigned to the 27th Field Artillery, I was one of the guys assigned to headquarters battery. I was a PFC at the time, taking line item reports, doing ammo resupply, etc. I did not care for that too much.

The tent that I was in had this guy who was the colonel’s driver, just a coincidence. This guy was always talking, “Me and the colonel did this, me and the colonel did that.” I did not even know who the colonel was. I never saw him, did not know his name, didn’t know anything about him.

This guy was a little bit of a character. From Florida. One night he and somebody else got the colonel’s jeep by telling someone in the motor pool that the colonel wanted the jeep. He wanted to go into town and get some boom-boom. He was drunk at the time and the other guy was drunk. On the way to town they ran off the road into a drainage ditch by rice paddies. The jeep was wrecked and they could not get it out of the ditch. They got on the horn and said they were out with the colonel and under enemy attack. They gave a half-ass location, not a map coordinate but a spot along the road outside the gate.

Ernie Dublisky was running the service battery at battalion and remembers the incident. “Over the radio it really sounded like he was under attack. Colonel Munnelly told me to gather a group of guys and a couple of gunned vehicles and go get him. When we got there it was apparent the guy was drunk and had put people in danger. Going out into the boonies at night was dangerous and it took guts … all over a goddamn drunk. We were pissed and I started to beat the crap out of the guy. My jeep driver, Spec 4 Krieger, pulled me off and said, ‘Officers aren’t supposed to do this sort of thing. Let us take care of it.’ I said, ‘OK.’ Then they beat the crap out of him.”

Soon the guy was brought back into our hooch. The colonel came in, which was the first time I ever saw him, and read the guy the riot act.

Reflecting on the incident today, Col. Munnelly says “The radio net was monitored by the command net of our supported 4th Infantry Division. It was enormously embarrassing.” Then he says simply, “Somehow the perpetrator got rouged up. Courts-martial charges ensued.”

A couple days later the sergeant major approached me and asked if I wanted to drive the colonel. I did not know anything about the job, but you have a certain amount of restlessness and you want a little change of pace from just going all day between your hooch and operations tents.

When he asked if I wanted to drive for the colonel I said, “Why me?”

He indicated that the colonel wanted someone with an education. Not that I’m a rocket scientist, but they went through the records and I might have been the only guy with over six months to go who had graduated from college.

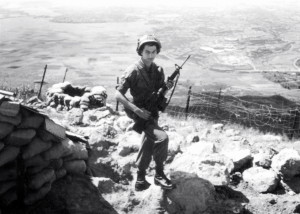

I drove for him from the middle of April ‘67 – I had been there about a month or so – until he left in August of ’67. Most of the time it was just the two of us in the jeep. We had the two radios in the back with two whip antennas. We had our subdued insignia on, but who cares whether it’s subdued or not, you’re an important guy in this jeep. This isn’t a laundry run with two whip antennas on it. People observing would know this is someone important driving up the highway now, let’s do something about it.

One time we took a ride up to Qui Nhan which was where B battery was at the time. It was a long haul, because headquarters was in Tuy Hoa. We took highway 1 up to Tuy Hoa, just the two of us. We visited A battery along the way, and another battery between Tuy Hoa and Song Cao, an 8 inch unit of the 6/32nd or 6/36th, that was attached to us, and then on up to Qui Nhan.

It was quite a ride up to B battery. B battery had the high ground and the guns were spread out a bit. From there it looked down on the whole area of fire. It was not a flat ride, the elevation shot up quite a bit after Song Cao. I don’t want to say it was in the middle of nowhere, but a lot of the time you felt vulnerable. You always wanted to know where you were and who could support you if you were fired upon or you had to call in choppers or artillery support. I used to think of it as a ride through the pretty country, a nice pleasant day, nobody bothering me. But the highway was interdicted, you’d see holes in the highway where you’d have to almost stop to negotiate them, and you’d think I might be in somebody’s sights right now, I’m gonna die in however long it takes for the round to hit me in the head, that’s how much time I have. You just scrunch down a little bit, say your three Hail Mary’s and just keep on going. Nothing happened, but the colonel said to me at the end, “How many command detonated mines you think we ran over that did not detonate?” There had to be some. Some Vietnamese guy must have said, “Oh shit,” because a wire came loose as we just drove over it.

I felt very fortunate. I was a young guy, I didn’t know any better, you’re drafted, you go through basic and AIT. No other training and you ship out and you go someplace and you’re with a bunch of soldiers, some your age, some enlisted, some you like and some you don’t like. I was with a lot of guys from the south. I have an Italian last name and I’m from New York, so in the culture wars I was automatically the enemy. I was not a yahoo like a bunch of people. I had a different demeanor about me than some of the fellas I was with. So it was a nice experience for me to hook up with somebody like the colonel because he was a very decent man, very down to earth, approachable. I was a great thing for me.

I don’t know what the conditions of the battalion were prior to me getting there, but I remember one time when I started driving for him he was having a command inspection in one of the firing batteries. I thought to myself, a command inspection, that’s something you do in basic training or AIT; why are you doing it in the middle of a combat zone where they have to lay out their boots and uniforms. I thought it was penny ante. Of course I didn’t say that. I might have asked him coming back, “How come you did that? Doesn’t that detract from readiness when everybody’s spending time doing this?”

He said that the situation that he saw when he first got there was people with ragged boots, ripped uniforms. And people were not doing their jobs. He was the battalion commander with the responsibility to make sure that people are well fed, that they have uniforms, boots, the tents don’t have rain coming in and you got your canteen, your pistol belt, and all the other stuff and you shouldn’t look like a homeless man because you’re out in the field. He addressed himself to that and whatever people needed to be effective they got.

My initial thing was that it looked like harassment and penny ante, but it wasn’t. He had the mature mindset, he had been through this before, and he knew what it was like in the field with bad equipment, and he didn’t like his soldiers being taken care of like that. He did something about it. When he explained it that way, all you could do was respect the guy.

You’re a young guy, and you think these things are automatically done. My five months of military experience up to that time there was always food in the mess hall, everybody always had a uniform, everybody had boots, and I just thought that whoever is supposed to be taking care of things, is taking care of things. But then you go into the middle of nowhere and you find out that maybe the supply sergeant isn’t doing it, the colonel isn’t addressing himself to the men, who knows what it is? It was broken and he fixed it.

He said to me when he was leaving, “What do you want to do when I’m gone?”

I said, “Maybe I’ll drive for your replacement.”

He said, “You might not like doing that because you are used to working with one person and you are going to be working with someone else. Sometimes it’s not a good mix. The Army spent a lot of money training you to do FDC work. If it does not work out driving for the new colonel, why don’t you go out to a firing battery and do what you were trained to do?” He was very serious, looked me in the eye. That weighed with me

I did not know what he was talking about until I started driving for the second person. I did not care for his style. I felt like I was his valet. I thought, I’m in a combat zone, but more like a chauffer. I drove for the new guy maybe a week or so and then I went to the sergeant major and said maybe I should go out to a firing batter. They said OK and checked around. I went down to Nha Trang and became the chief of a two gun crew. It was the special forces headquarters, and we shot for the special forces teams that were in that area. The guys on the guns would rotate from the 5th battalion firing batteries to my crew in Nha Trang because it had more creature comforts.

When I drove for Colonel Munnelly he and I would saddle up and we’d sometimes have a guy with an M60 machinegun for extra security. But a lot of the time it was just the two of us. We’d go out into the field a lot. He liked to see things from the ground and I got to see a little bit of the country. It was good for me. I really liked him a lot.

Have you read Surplus: The Long Arm of Vietnam, the companion book to Seven in a Jeep?

Have you read Surplus: The Long Arm of Vietnam, the companion book to Seven in a Jeep?