Starting Over

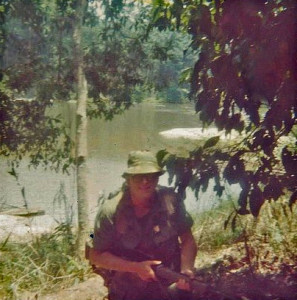

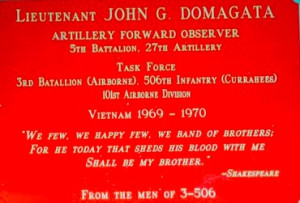

After four months with the ARVNs (South Vietnamese Forces) I got assigned as a forward observer to the 3/506 Infantry of the 101st Airborne. Because I am not infantry and I am not airborne. I’m an outsider again and I gotta start from scratch. Also, I still look like I’m 17.

I go out on operations, I don’t screw up and I get to know the team I’m working with. Then a different company rotates to the field, which means I start from scratch – again. Those initial operations with the 101st were bad, I mean I was an outcast.

To make it worse there was a shortage of forward observers. When the infantry company would rotate to a firebase or the rear for a stand down, I would rotate to another company headed for the field. I had more field time than anybody in the infantry. That’s one reason I burned through radio operators. They’d see all these guys going in and we never got to go in.

It took a month before word got around that hey this guy is actually good and does things right, fast, and knows what he’s doing. Early on I got to call in naval gunfire from the battleship New Jersey. Phan Thiet was the New Jersey’s final run before she left for home. (The battleship New Jersey departed the Phan Thiet area for Japan on April 1, 1969.) That went a long way to showing what I could do. Remember I’m not a green forward observer. I’ve been out with ARVN troops for four months calling in long range artillery, because we were hardly ever near a 105 battery.

Now I’m all over the place, in the Lee Hong Fong forest, up in the mountain jungles, and down around Titty Mountain – firing out of Sherry, Sandy or a platoon of guns on a hip shoot. We’d even go way up north along the coast around Song Mau with a couple guns from Charlie Battery. I was on and off in the field with the 3/506 all the way through September, five months straight.

Search and Garden

Now one war story, the only one I remember. We’re out in the mountains following a band of Viet Cong through thick jungle, and every once in awhile boom there’s a big open area the size of four football fields plowed in neat furrows growing corn and all kinds of squash. We’re on our third day following the VC and this is our third garden. Instead of “search and destroy” we started calling this operation “search and garden.” Well this garden has watermelon and it’s hot and the watermelons are cold and the guys are carrying them on their shoulders. It’s crazy.

It turns into an ambush. Our point guys are under fire from the jungle and you can’t see where it’s coming from. I am a little behind them with the platoon leader and company commander. We’re in the worst possible situation to bring in artillery because we’re in the mountains, meaning you’ve got altitude to worry about, and we’re on the target line (between the target and the howitzers and therefore exposed to range dispersion). I call in a first round smoke and it’s pretty close. I adjust the second smoke round away from us and it pops right behind the enemy, which is perfect. The guys are yelling “It’s right where we want it. It’s right behind them. We’ve got them pinned down. Yaa.” I call for all the guns to fire high explosive on that setting – BATTERY REPEAT HE. Instead of landing on the VC the rounds come down right on top of us. I see one of our guys get blown twenty feet in the air. I’m seeing this guy and thinking, Holy shit. Right away I call a CHECK FIRE.

We were lucky. When the VC saw artillery coming in they took off. The round that blew our guy in the air hit soft, plowed soil from the garden and buried itself before detonating. It gave him a ride but nothing serious. And nobody took shrapnel from the other rounds. He was the only one hurt and medevac’d out. If we were in a treed area, or on regular hard ground, there would have been a lot of shrapnel injury, but because we were in this this big freaking garden area, the round penetrated into the ground before it went off.

Then of course the investigation begins, interviews like crazy. We had a colonel who was the commanding officer of Task Force South come flying in, another colonel from Phan Rang and all kinds of other people. With them was the artillery commander of the battery that fired the rounds (Delta Battery of the 2/320th Artillery at LZ Betty attached to the 101st). They are interviewing everyone right on the spot. Everyone is validating that what I did, and the way I did it, verifying that I did not do anything wrong. The first round was here, the second round was there, and I called high explosive in on the back side of the second smoke round. I just said REPEAT HE, right on top of the last smoke around, no adjustment.

We spend the night and the morning, and another group comes to do more interviews. Everybody who is important – the commanding officer, the company commander, my radio operator and the commanding officer’s radio guy – know that I did this right. But the troops only know rounds landed on top of them and blew one of their guys up. I’m the artillery guy, and I’m not airborne. When I see our injured guy with his neck brace on I cannot look him in the eye. Nobody would look me in the eye either, and for awhile I think they were going to turn on me.

The mission carries on and I don’t hear anything more about it. But do you ask what happened or do you let it go? What do you do? I’m 21 years old; I let it go. Until I got home and then it comes back, and comes back, and won’t leave me alone. It took me twenty years to resolve. I went to the National Archives and got the after-action reports for the artillery and 3/506. I found out that a batch of smoke rounds was bad and was shooting long. This was not the first incident, it happened in another place before me. As a result they pulled all those rounds. But who’s gonna tell the young second lieutenant who’s out as a forward observer that he might want to know so he can sleep better.

They should have pulled those smoke round after the first incident. The second time with me should never have happened. You cannot believe the pucker factor when those big 105 rounds are landing all around you. Mortars are one thing, and I have survived some mortar attacks and those are frightening enough, but this was (laughs) crazy. Rule number one is don’t be on the gun target line. But we did not have any choice, that’s where we were at. There was no secondary battery to call. It was like, We need rounds now, let’s get them in. They did get us the rounds quick, first round smoke, second round smoke, then BANG. I can sti

ll hear those rounds coming in over our heads and down on us. That’s something you never forget.

I lost my radio guy because of this. He said, “I cannot be out here anymore.” The artillery radio operator was an artillery guy, and he had to be a volunteer. He said, “I ain’t volunteering anymore.” I went through a lot of radio operators because they’d get freaked out.

Viet Cong Elephants

Another crazy story. I can remember crazy things, but not warrior stuff, except for those bad smoke rounds. We are in the highest mountains and the thickest jungle you can imagine trying to catch up with a unit of Viet Cong. Typically when you are following a trail you have your guys out to the left and the right, and maybe some guys in the middle. But this trail was along a cliff edge two feet wide, straight up a couple hundred feet and straight down 1000 feet. All of a sudden we see these things that look like cannonballs on the trail. What in the hell is this? It was nothing you would ever guess – elephant shit. So elephants had been walking down this narrow trail that I am scared to walk on: you can’t go one way because it’s a wall and the other way is a sheer cliff to your death. Viet Cong elephants loaded with stuff had just gone down this trail, like Hannibal going through the Alps, and you think, How on earth? No, we never caught up with them. They were fast, those Viet Cong elephants.